ONLINE LECTURE MARCH 25 – Sideways Filmmaking

“Chris Marker brings to his films an absolutely new notion of montage that I will call “horizontal,” as opposed to traditional montage that plays out with the sense of duration through the relationship of shot to shot. Here, a given image doesn’t refer to the one that preceded it or the one that will follow, but rather it refers laterally, in some way, to what is said.”

Andre Bazin, 1958

Words and images have been combined in film for about ninety odd years. But it is still an uneasy marriage. The emphasis on synch sound, a technique that naturalizes the relationship between sound and image as emerging simultaneous from a real world source, is such a given that it pulls attention away from the variety of potential alternative relationships between the visual and the sound track, and in particular for documentary, the text. The history of European pedagogy, where fine arts and humanities are separated, adds to the difficulty.

If the classic documentary form is akin to the slide/lecture form, where you see a series image and hear how to understand those images, carefully pruning out the other readings, removing, ironically, what Barthes called the punctum. What interests me is how the “essay film” is an interplay between a non-fiction written form and a visual or audio-visual one, and explicitly, a trying out of new ways of making meaning. If one can imagine most non-fiction films fall on a spectrum where at one end the text is used to support, explain and valorize the image, to another pole where the image is an illustration of the text, then the essay film takes off on another vector, where the relationship is aleatory, exposed as partial and evocative, rather than totalizing or definitive. For me as a practitioner, the essay form is an opportunity to create a different set of relationships between sound and image.

Since Montaigne a literary essay is a written trace of a discursive thinking process, a ponder on an issue, but one that is willing to take side trips. One of the first makers to deploy the essay form in film was the French documentarian Chris Marker. An early example is his Letters from Siberia (1958).

Nora Alter notes that the audience can’t distinguish whether sound is cut to picture or vice versa in Letters from Siberia. “…the relationship between the sound track and the image track is continuously questioned throughout Letters from Siberia.” Take a look at the clip and ask yourself how the repetition of the shot and the alternative voice-overs works. What exactly is it questioning? What does it make us think about the way we understand the relationship between soundtrack and image track in a documentary film?

Philip Lopate, trying to define the essay film when it was still an emerging form, noted that it was possible to do an essay film where the text pre-exists the film, for example Jean Cayrol’s text for Jean Resnais’s Night and Fog, but that for him it is the back and forth that stands out. Certainly, it is hard to imagine that Marker made his film any other way than by cutting some footage, putting in some sound, then cutting some more in response, in an iterative process. As a kind of Gedenken experiment, take a look at this chunk of narration from Sans Soleil (1983):

He used to write to me: the Sahel is not only what is shown of it when it is too late; it’s a land that drought seeps into like water into a leaking boat. The animals resurrected for the time of a carnival in Bissau will be petrified again, as soon as a new attack has changed the savannah into a desert. This is a state of survival that the rich countries have forgotten, with one exception—you win—Japan. My constant comings and goings are not a search for contrasts; they are a journey to the two extreme poles of survival.

He spoke to me of Sei Shonagon, a lady in waiting to Princess Sadako at the beginning of the 11th century, in the Heian period. Do we ever know where history is really made? Rulers ruled and used complicated strategies to fight one another. Real power was in the hands of a family of hereditary regents; the emperor’s court had become nothing more than a place of intrigues and intellectual games. But by learning to draw a sort of melancholy comfort from the contemplation of the tiniest things this small group of idlers left a mark on Japanese sensibility much deeper than the mediocre thundering of the politicians. Shonagon had a passion for lists: the list of ‘elegant things,’ ‘distressing things,’ or even of ‘things not worth doing.’ One day she got the idea of drawing up a list of ‘things that quicken the heart.’ Not a bad criterion I realize when I’m filming; I bow to the economic miracle, but what I want to show you are the neighborhood celebrations.

It is hard to say why it works for Marker to combine an image of a nuclear missile being launched from a US submarine with a discussion of the Japanese court in the 10th century. Perhaps we can imagine the conceptual link between the Heian imperium and the American version. Or maybe it is the brilliant blue of the sea and the white of the missile emerging from the waves… The mind is neither in the eye, nor the ear, but in a mental space, one that Bazin terms the space of intelligence, and that Gilles Deleuze might call the space of the concept. (Cinema I)

But it is also a space of affect based on the development of a poly-rhythmic experience. If Harry Watt & Basil Wright’s 1936 classic Night Mail, a rhythmic documentary cut to D.H. Auden’s poetry, is canonical, it is a hard model to follow. For the filmmaker, going back and forth over and over, altering the wording and cadence and then going back and tweaking the visuals to create a certain shared rhythm is essential. The practice is akin to jazz, where players take a clue from each other and step in and out, rather than the classical model with a tight score and impeccable timing.

What are the issues at hand? One of the clearest thing about the essay film is that fragments are evocative, that pieces of film have meaning outside of their original context. In Marker’s Sans Soleil the story is set in Japan, but goes all over the world following Marker’s own journeys. As the narration notes, in a way the 16mm shots are his thoughts. As Nora Alter notes, Harun Farocki also repurposes footage, in his case often from industrial films that he’s worked on as part of his day job.

In class we took a close look at the opening of Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989) shots of a wave machine in an oceanography lab. In the VO Farocki talks about how the water “unfetters the gaze.” The gap between this footage of a laboratory and a voice-over contemplating the limits of vision seems wide, but as viewed, it is still close enough to create a force field of sorts between the text and the image.

This area of film-making, where images can take on new meanings in relation to our own contemplation is a key one in our era gains special significance in our time of globalized capital flows, and massive ecological disaster especially, as Ursula Biemann notes through its ability to “organize complexities,” without doing them the injustice of simplifying them:

Not unlike transnationalism, the essay practices dislocation, it moves across national boundaries and continents and ties together disparate places through a particular logic. In the essay, it is the voice-over narration that ties the pieces together in a string of reflections that follow a subjective logic. The narration in the essay, the authorial voice, is clearly situated in that it acknowledges a very personal view, a female migrant position, a white workers position, a queer black position etc., and this distinguishes it from a documentarian voice or a scientific voice. The narration is situated in terms of identification but it isn’t located in a geographic sense. It’s the translocal voice of a mobile, traveling subject that doesn’t belong to the place it describes but knows enough about it to unravel its layers of meaning. But the mere gathering of information and facts is hardly of interest, for the essay doesn’t believe in the representability of truth. The essayist intention lies much rather in a reflection on the world and the social order, and it does so by arranging the material into a particular field of connections. In other words, the essayist approach is not about documenting realities but about organizing complexities.

Ursula Biemann Performing Borders: The Transnational Video

In the syllabus I titled this discussion “Documentary by Other Means.” I look forward to hearing from you all how you can bring those means to bear on our complex predicament, one that has left us, as makers, without cameras, without crew, and stuck in place.

Marty Lucas, March 25, 2020

ONLINE LECTURE – APRIL 7th

Tech Talk Slides – here are the slides from the online lecture. The video version is on Vimeo at

the password is IMADOC2

ONLINE LECTURE April 14th

There were two discussions. The first was about Bertold Brecht’s ideas of “epic theater” and how they might apply to documentary filmmaking.

The other was a look at color spaces, the graphic visualization of what colors can be by the human eye, and reproduced in different forms.

ONLINE LECTURE APRIL 21st

Here are the slides from the lecture segment that dealt with Fair Use and Intellectual Property.

I also suggest taking a look at RIP Remix Manifesto, a documentary that contemplates property rights from the POV of Girl Talk. See: https://archive.org/details/RipRemixManifesto

In particular, look at section 3, “Culture is always built on the past.”

ONLINE LECTURE APRIL 29th

DOC II • APRIL 29

In this class I want to continue the discussion I’ve been calling Documentary by Other Means.

I would like to look at the beginning of Resisting Paradise, a 2003 film by Barbara Hammer to think about what it means to ask questions about beauty in times of troubles. (You can find the opening in the movies section of this site.)

I want to end the discussion with a brief look at issues of color correction in production, and the assumptions we make when we assume there is a “correct” color that we have either achieved or not.

To start the discussion I would like to go back to Immanuel Kant, who is an important transitional figure, completing, in a certain way, the philosophical projects of the Enlightment, and setting the stakes for modern discussions of aesthetics in his Critique of Judgement (1790) and his Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime(1764).

Kant wrote about beauty not as a quality inherent in an object or a person, but as a response from the viewer. This response is disinterested, and the contemplation of the object gives pleasure. The judgement we make when we decide something is beautiful or not is a judgement of taste, not the outcome of logical reasoning. He also claims that the elements that evoke the reaction are formal ones, so that in a way the formal qualities trumps content when it comes to categorizing something as beautiful. For Kant, even though the judgement is personal, it is also universal. In other words, he thinks that discerning minds will make judgements of beauty that correspond. This means that the standards are not objective exactly, but somehow universal.

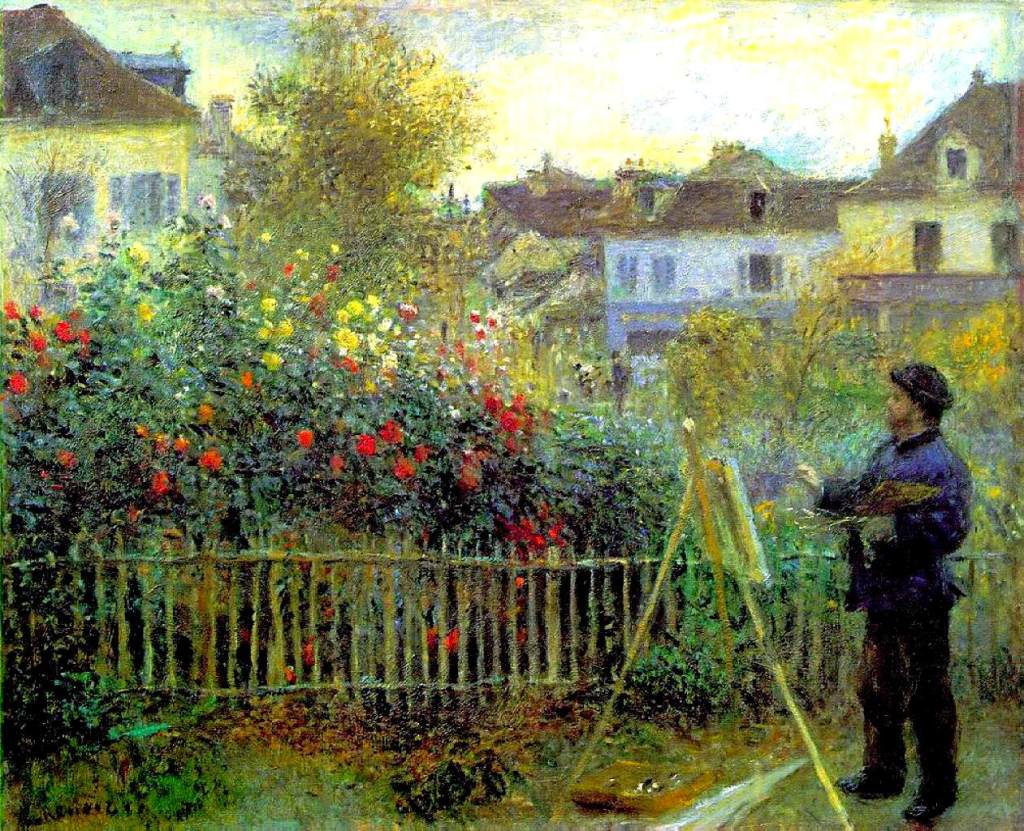

Kant didn’t care much about color. But in the late 19th century a new group of painters became more interested exactly in the real world and our affective response to it. They were pleine-aire painters, not always working in the studio. Their subjects were every day. The Impressionists are still some of the most popular of painters.

The very term impressionism suggests that the effect of the painting on the viewer, following the effect of the light on the subject, and the painter’s efforts to convey that impression, have become central to art, as opposed to the concern artists had in the mid-19th century to offer paintings as realistic portrayals, whether of the world, of people, or of important moments in history, etc. Impressionist painters included Manet, Monet, Mary Cassatt, Sisely and Renoir.

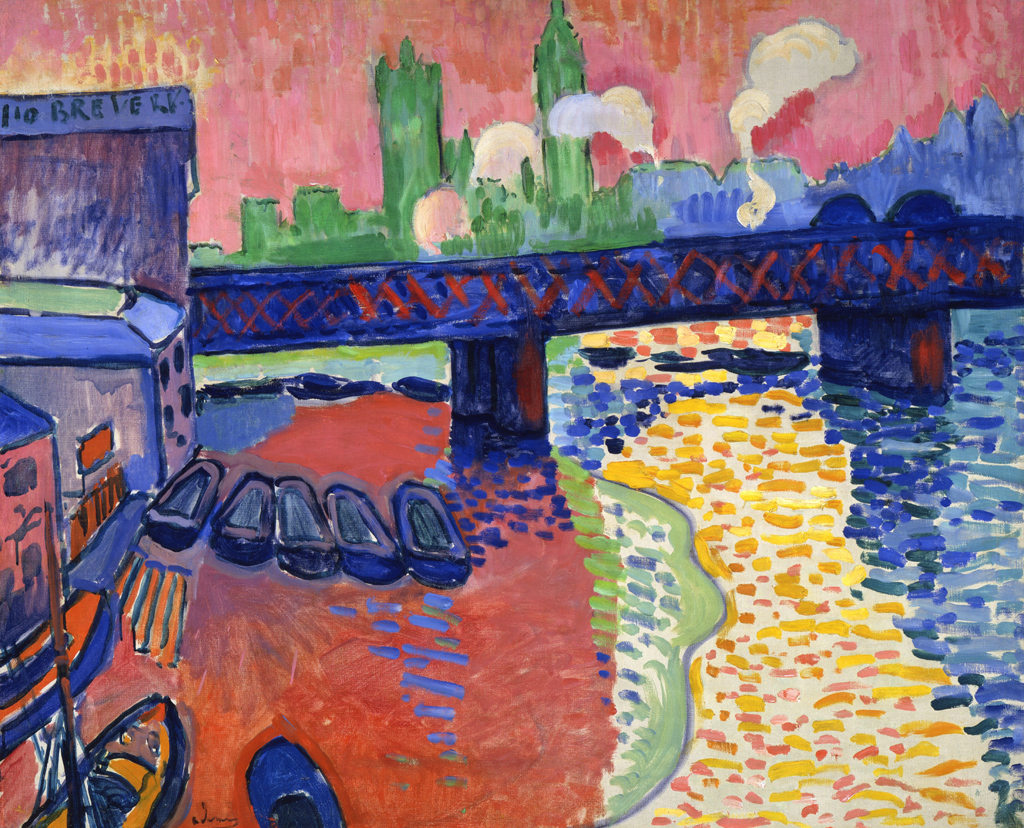

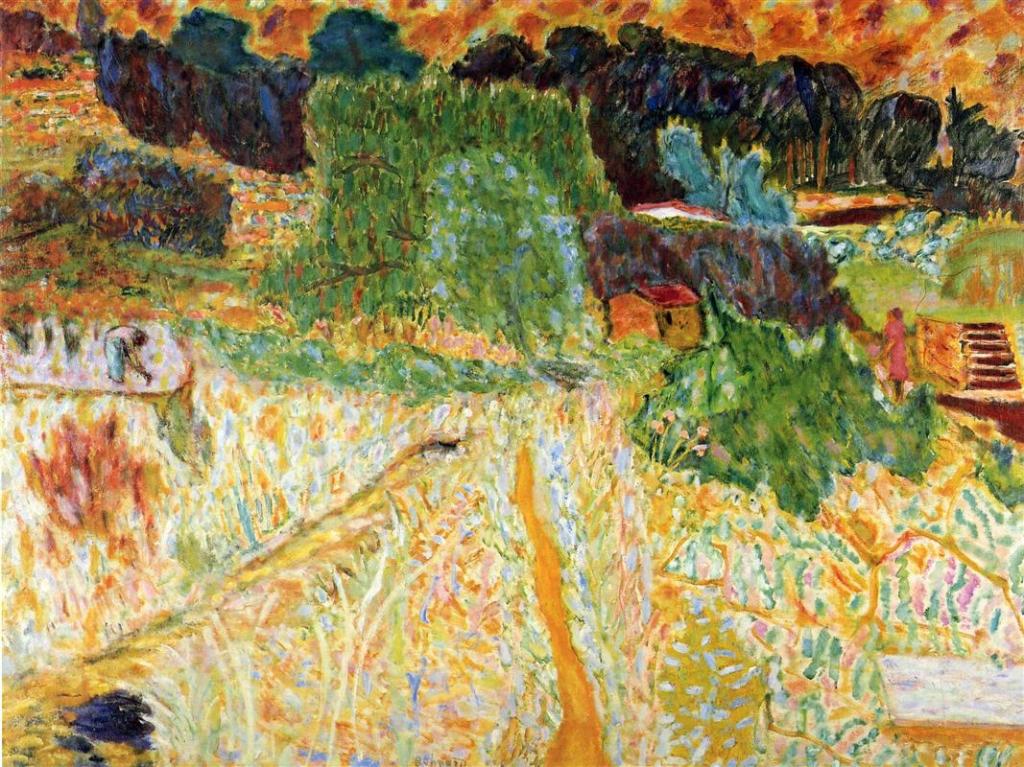

The Impressionists were followed in quick succession by new groups of artists, Post-Impressionists who included Cezanne, Gaughin and Van Gogh (roughly 1885-1905) and then the Fauvists, notably Henri Matisse and André Derain.

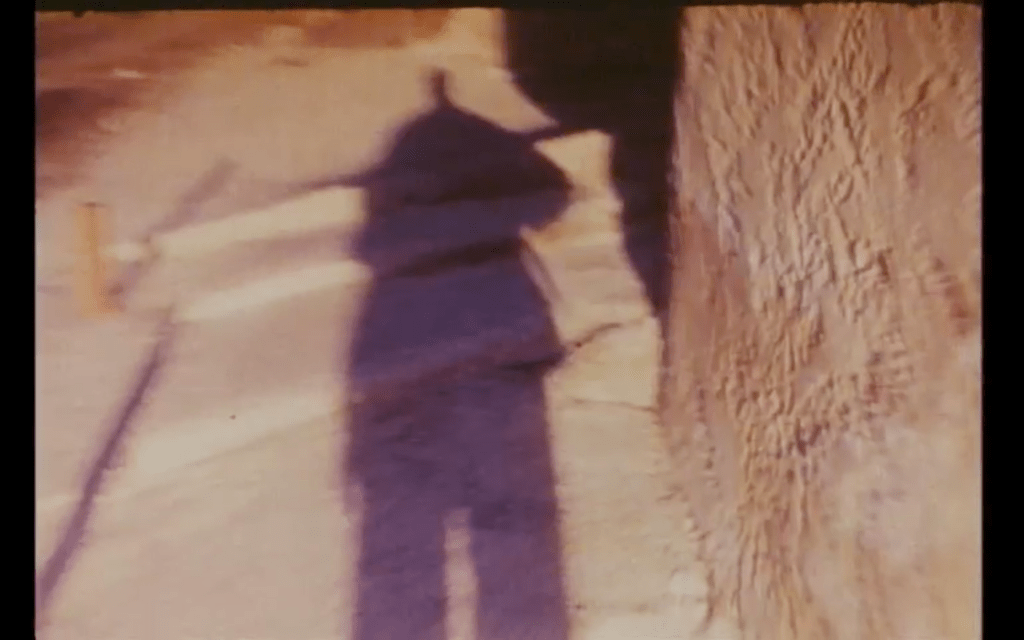

Barbara Hammer’s film explores a much later period, that of the World War 2. On an artist’s residency in Southern France, she is provoked by the outbreak of war in the Balkans to rethink her own interest in the role of beauty in art. Hammer herself studied painting before becoming a filmmaker.

The specific area where she stayed was a major route for those seeking to escape the Nazis to Spain. It was also where a few French painters, including Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard chose to stay, rather than fleeing to safety as many of their younger counterparts did. In her film Hammer uses a variety of techniques to explore the allure of Southern France as a place where the captivating quality of the light offers a kind of transcendent beauty, and contrasts that with the horrors of the war.

The opening segment of her film puts on display several of the techniques she uses, including compositing, shooting through glass while painting on it, and altered shutter speeds. Take a look and ask yourself how these techniques serve her larger goals, and the difficult questions she is trying to address.

In the online session, I mentioned one particular set of questions that emerge around the illusion of realism created by the camera, the illusion that you are seeing a realistic scene based on what was filmed (an illusion particularly prevalent in documentary) and the fact that what viewers are in fact seeing is a flat screen comprised of thousands of individual pixels. Artists like Matisse explored the tension between the way that color and color fields tend to emphasize the picture plane, and detract from a sense of depth while line tends to help promote the sense of depth. Hammer, who has a background in painting and in experimental film, is highly aware of this kind of tension.

You have to look at her work and make up your own mind about what she is doing. One way to think about it is to say that she is exposing that tension, rather than using the tools of line and color to promote a sense of complacency about the world that we see (and the one we can’t).

This is relevant for me when I come to deploying the tools of “color correction” in film production. While close control of color values and exposures in a film use to be the province of cinematographers and high end industrial film production, it is today in anyone’s hands. However, there are assumptions built into those tools as well, assumptions about the need for consistence, about the value of certain kinds of cinematic looks, etc. It is up to each of us as a maker to assess these tools both on an artistic and on an ideological level, and make up our own minds how we want to use them.

A Short Intro to Color Correction for Premiere Pro

ONLINE LECTURE MAY 6th

IMA DOC 2 – Week 13

Myth and Productive Speech

Film Language is designed to produce a certain idea about reality, or even a confirm a certain set of assumptions about the nature of reality, its physical nature, as in our sense of space, its subjective nature, in terms of its assumptions about what human nature is.

When we assemble images we both reproduce and play with those codes. If you think of it in terms of language, or of a language, we use the grammar, but we create new meanings.

Or do we? There are countries where there are a group of specialists deciding what should be part of a language and what shouldn’t, notably Spain and France.

But what about “new usages?” What kind of new meanings can be created? Where does the New come from?

I would argue that without the new, we face a world that moves toward a kind of re-hashed fascism. Right now we live in a world where the construction of myth takes place on a daily basis. In the long run facts beat myths, but in the short run, that doesn’t always work. And our job as documentary filmmakers means working with the reality that faces us.

With this in mind I’d like to recall Roland Barthes’ Mythologies (which I’ve put in the Reading.) For Barthes, myth is a complex sign system, one he sees as offering a kind of semiological slight of hand, one where meanings invoked, but not asked to stand up to rational inspection. “We must here recall that the materials of mythical speech (the language itself, photography, painting, posters, rituals, objects, etc.), however different at the start, are reduced to a pure signifying function as soon as they are caught by myth.” (114) It doesn’t have to stand up, because it is not any longer using the signs to point back to the reality they are the referents for, but rather are used as the building blocks for the myth, which Barthes calls a meta-language.

I am at the barber’s, and a copy of Paris-Match is offered to me. On the cover, a young Negro in a French uniform is saluting, with his eyes uplifted, probably fixed on a fold of the tricolour. All this is the meaning of the picture. But, whether naively or not, I see very well what it signifies to me: that France is a great Empire, that all her sons, without any color discrimination, faithfully serve under her flag, and that there is no better answer to the detractors of an alleged colonialism than the zeal shown by this Negro in serving his so-called oppressors. (116)

Barthes calls myth depoliticized speech. This may seem odd, because we think of the spoutings of someone like Trump as political. But he is constantly rewriting history, so any real history goes missing. So it naturalizes things that are actually contestable. For example, Make America Great Again. If you start to unpack that, you have a set of assumptions about the nature of greatness, the unspoken nature of privilege, deals between rulers and ruled, hidden histories of genocide and slavery, workers struggles, etc.

As a filmmaker, you can also engage with the language of myth, as Barthes goes on to note, but you need to understand what you’re up to. Not reproducing a myth, but engaging with language on the level of production. Barthes uses the example of the difference between the way a woodcutter uses the word tree and the rest of us. For the woodcutter, the tree is a space of production. They turn it into lumber. As Marx notes, that is the core of use value, of the labor theory of value. But for others, we reference the word tree as an abstraction, as a word that signifies tree.

Thinking from this point of view I wanted to reference two films, the Khalil brothers’ Inaatse/se and Illinois Parables, by Deborah Stratman. Both films, in different ways, engage with myth and languages of power. Inaatse/se seeks to create a discussion on the level of indigenous traditional knowledge and introduces into documentary a prophetic mode. Stratman’s film is epic, a series of chapters that cover the history of Illinois since the coming of European settlers but it lays these moments out in a way that occupies the space of the mythologies that America creates for itself with a new discourse.

At a time when the classic fact-based notion of a documentary that will lay out the facts for an audience of citizens who will watch, debate, and then debate policy options is no longer viable – a time when fact-based discussion is denigrated, it is worth considering new forms of documentary speech and what they can offer us.

I would like to recall the Oberhausen Manifesto. Post-war German filmmakers saw a dilemma. In terms of a national cinema, Germany offered two options, one was to try to imitate the market leader, Hollywood, but without Hollywood’s resources. The other was to look back to the pre-war period. But that kind of nostalgia was basically a nostalgia for Fascism. The only valid answer was to create a new cinema.

THE OBERHAUSENHAUSEN MANIFESTO

The decline of conventional German cinema has taken away the economic incentive that imposed a method that, to us, goes against the ideology of film. A new style of film gets the chance to come alive.

Short movies by young German screenwriters, directors, and producers have achieved a number of international festival awards in the last few years and have earned respect from the international critics.

Their accomplishment and success has shown that the future of German films are in the hands of people who speak a new language of film. In Germany, as already in other countries, short film has become an educational and experimental field for feature films. We’re announcing our aspiration to create this new style of film.

Film needs to be more independent. Free from all usual conventions by the industry. Free from control of commercial partners. Free from the dictation of stakeholders.

We have detailed spiritual, structural, and economic ideas about the production of new German cinema. Together we’re willing to take any risk. Conventional film is dead. We believe in the new film.

Oberhausen, 28.2.1962

What can a new language for non-fiction film be in our time, when documentary is in one way quite popular, with big festivals and a growth of academic programs, but on the other offering few routes to distribution in a market where public television is a less significant force and visual attention economy is dominated by the likes of Amazon and Netflix?

The word ‘essay’ means to try something. And the work we’re seeing coming out of this class suggest that the effort is both effective and worth engaging in.

ANOTHER “HOW TO” VIDEO

In this video I attempt to go over how to think about color grading using (and not using) LUT’s and LOOKS, especially when shooting with “flat” profiles.

LECTURE 14 May 13th – Tech Talk

This is the video from the lecture that relates to building a VO track in the Premiere timeline, and to color correction with LUTs.